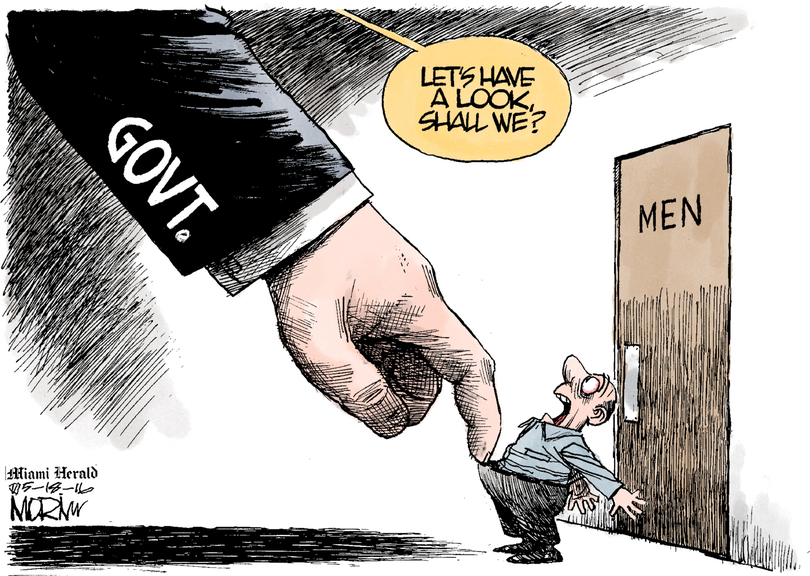

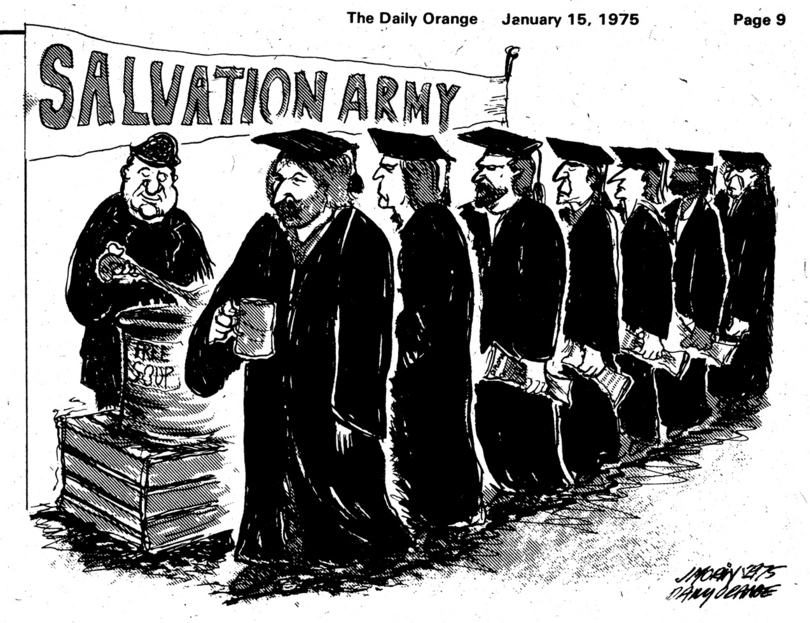

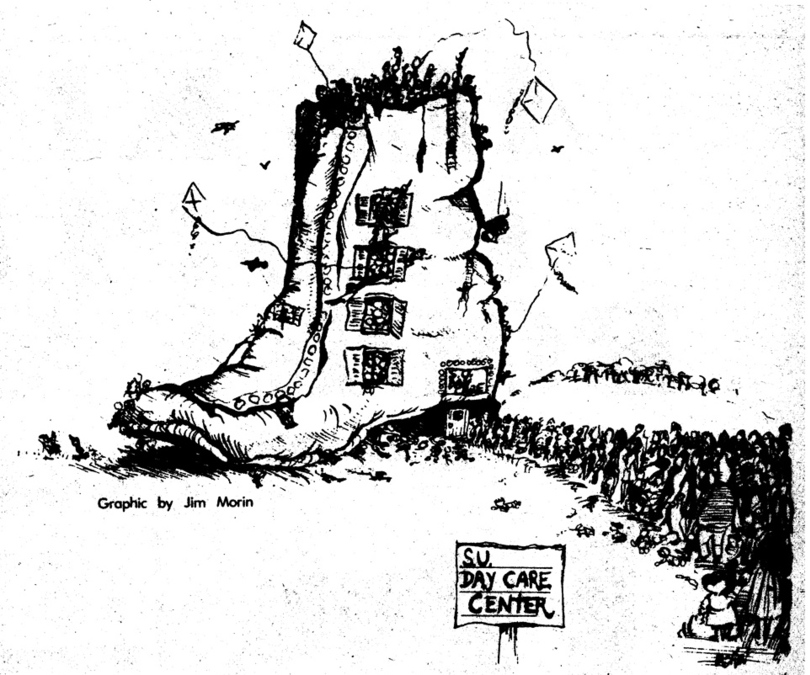

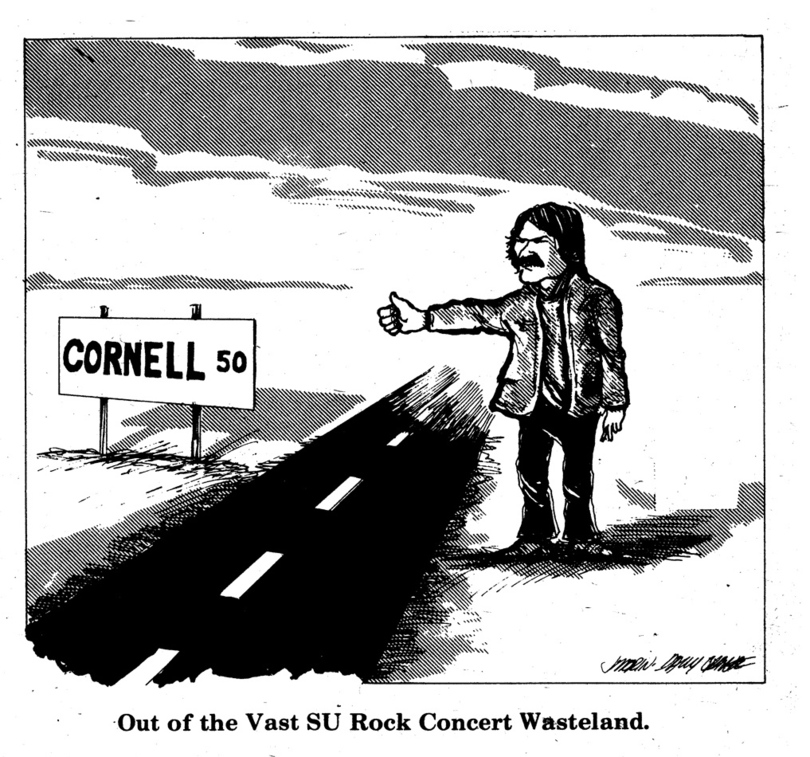

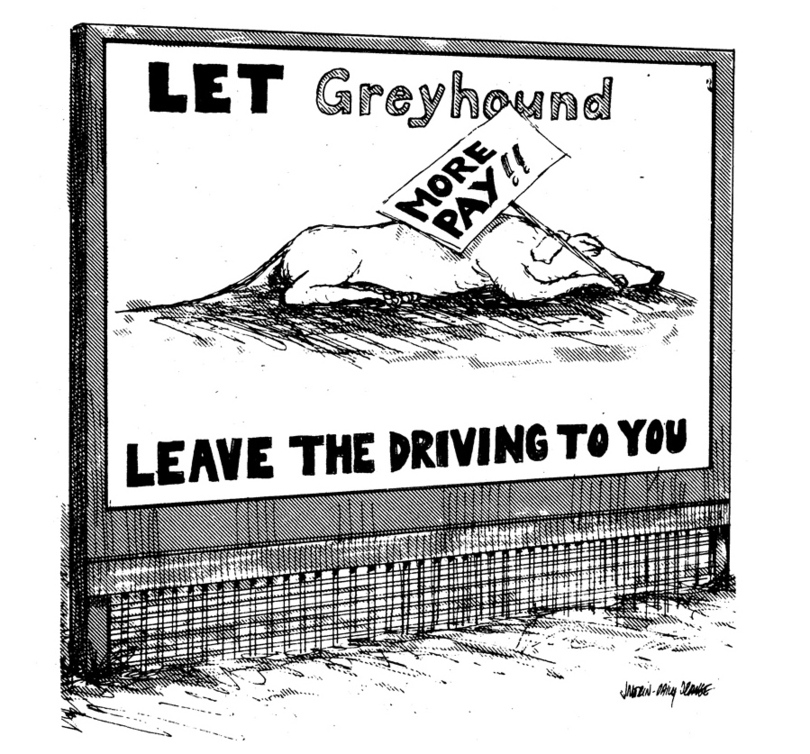

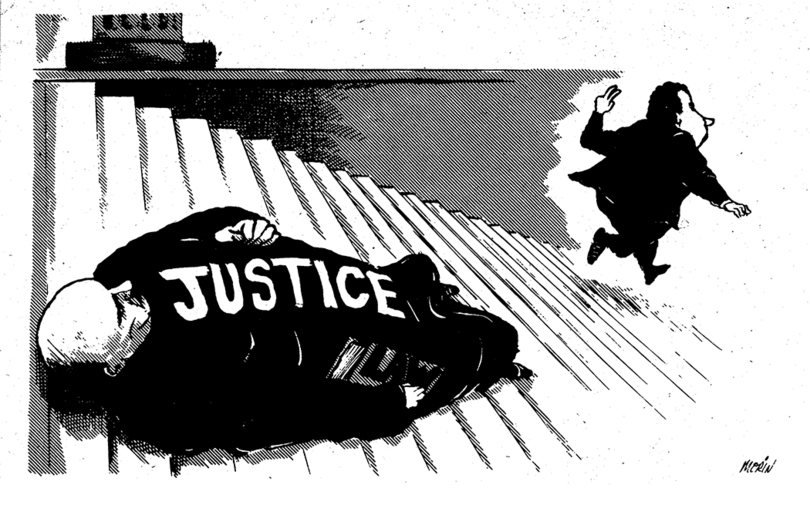

Newsmakers: As a student inspired by political unrest in the 70s, Jim Morin began drawing cartoons for The Daily Orange. Today, he’s a two-time Pulitzer winner.

UPDATED: May 8, 2017 at 11:20 a.m.

Jim Morin began drawing political cartoons at the behest of his mother. She worried her son, an illustration major, would graduate from Syracuse University without a job.

Last month, Morin won the 2017 Pulitzer Prize for editorial cartooning — his second in his 37-year career at the Miami Herald. It’s a victory Morin said would not have been possible without The Daily Orange and the jump-start it gave his career.

After just one semester studying liberal arts at SU, Morin (‘75) told his parents he would either transfer to the art school or drop out. He decided to make the switch and graduated with a degree in illustration and a minor in painting.

In 1974, Morin studied abroad in London as the Watergate scandal unfolded an ocean away. Morin’s new friends pressed him for his thoughts on the presidency and the state of the U.S. government, eventually piquing his interest in politics.

When he returned to the United States, Morin devoured newspapers and discovered the political cartoons that lived on the editorial page. After his mother noticed his interest, she suggested Morin draw his own. He returned to campus and set his sights on The D.O.

“I knew some people who worked at The D.O.,” Morin said. “And before I could approach them to ask if I could draw political cartoons for them, one of them approached me … which I thought was a good sign.”

Morin met with Mike Kelly, his first editor at The D.O., and began drawing two cartoons a week for the paper.

“By the second half of the year, I was doing five a week,” he said. “I just jumped my studies, I couldn’t care less.”

Morin equated his experience at The D.O. to working at a professional newspaper. He learned how to work with editors, deal with criticism and meet deadlines. He found a way to deal civilly with people with differing points of view and to not take offense when someone disagreed with a cartoon.

“Very early on, because of that routine I had at The D.O., I learned how to understand that you’re not going to be perfect every day,” Morin said. “If you do something that is not up to your standards, don’t sweat it. You can always improve it later on.”

Morin’s experience landed him editorial cartoonist positions at The Beaumont Enterprise in Texas and the Richmond Times-Dispatch in Virginia before he began his nearly four-decade career at the Miami Herald. He won his first Pulitzer Prize in 1996, which he described as a humbling experience.

“There is no other award like it,” Morin said. “It’s always shocking.”

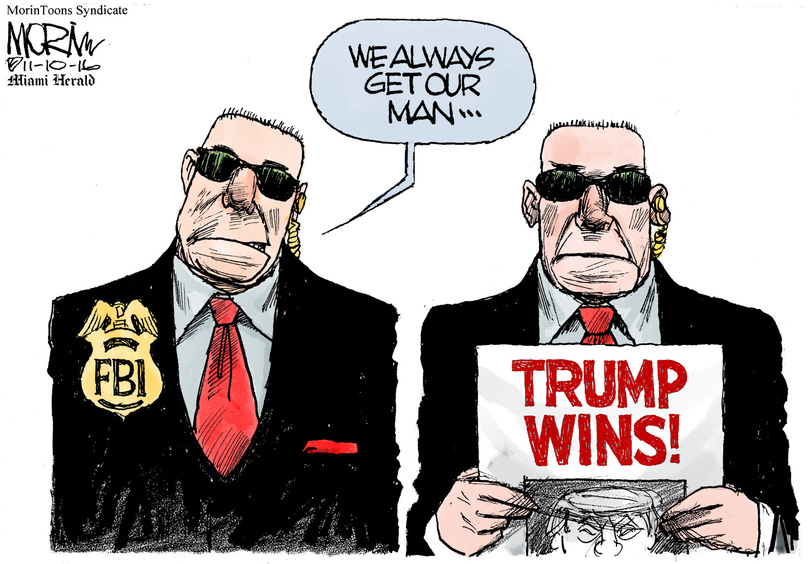

In 1996, the award came with less fanfare. Morin received phone calls and a few letters. When he won again in 2017, thanks to the growth of the internet and social media — namely Twitter and Facebook — Morin felt overwhelmed with praise. But the best part of the achievement, Morin said, is that it helped him reconnect with old friends.

“You meet people that you haven’t heard from in ages, two friends that just drifted apart, you get together again,” Morin said.

It is particularly gratifying to win the prize at this stage in his career, he said, especially because the win comes after an election year — something he claims is not his strong suit.

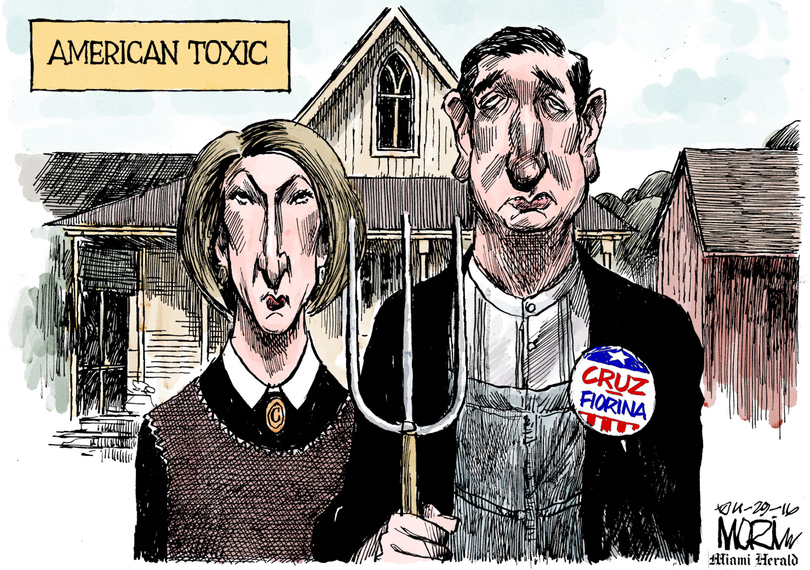

Morin said political campaigns include silliness, talk and personality. He prefers to draw issue-based cartoons.

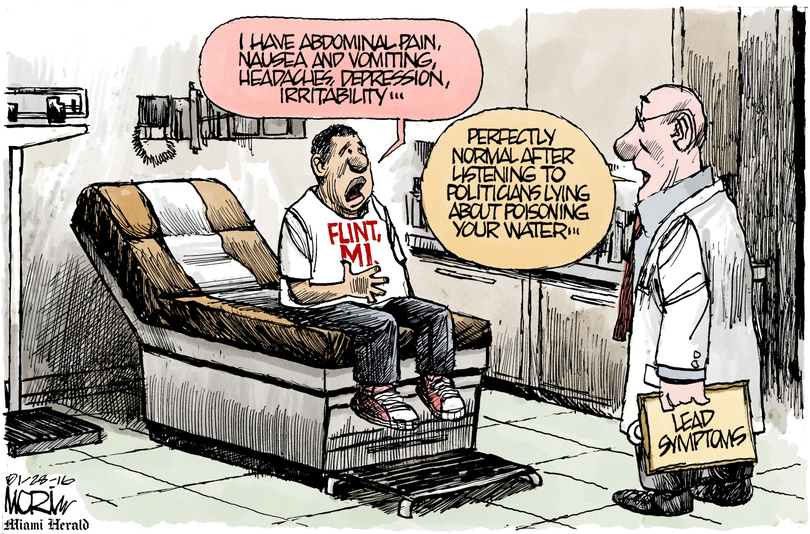

“I like (to draw) a nutcase with a nuclear weapon in North Korea or cutting a budget so poor people can’t get health care,” Morin said. “Things that really affect us as opposed to the show business, which is basically what a political campaign is.”

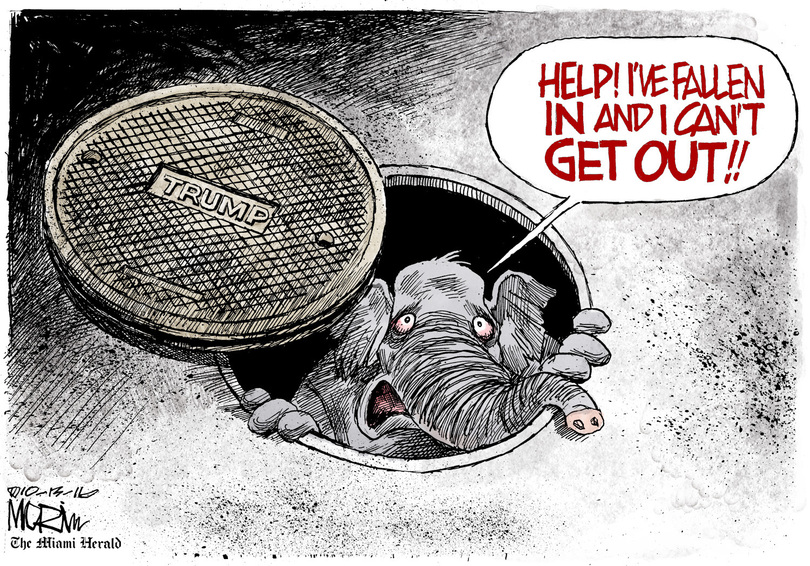

Between President Donald Trump’s administration and other world events, there’s always a topic to illustrate in a political cartoon, Morin said.

“Donald Trump is a joy,” Morin said. “Not for the country, but for (cartoonists).”

Morin used to draw his cartoon five days a week, but with newspaper budget cuts, he now typically works only four days a week. The number of full-time newspaper cartoonists has been reduced by half over the last ten years, he said. The ones who kept their jobs had established careers and made their work a part of the newspaper’s identity.

Morin doesn’t think the newspaper cartoon industry will completely disappear.

Sometimes cartoons can say more than written commentary.

“It’s quick to read but it also stays with you,” Morin said. “That image burns in your mind and there is nothing even remotely like it in the newspaper, and so that is why I think we are hanging around and haven’t gone yet.”

Published on May 5, 2017 at 10:24 pm

Contact Taylor: tnwatson@syr.edu